Deaf ASL Speakers Sign With a Philadelphia “Accent”

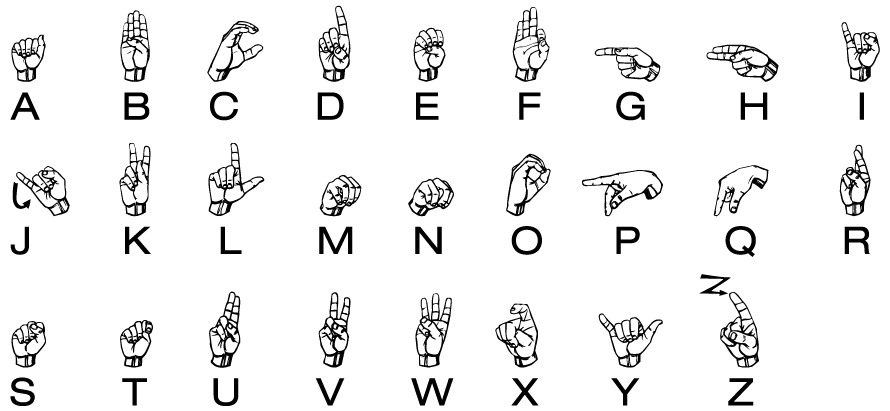

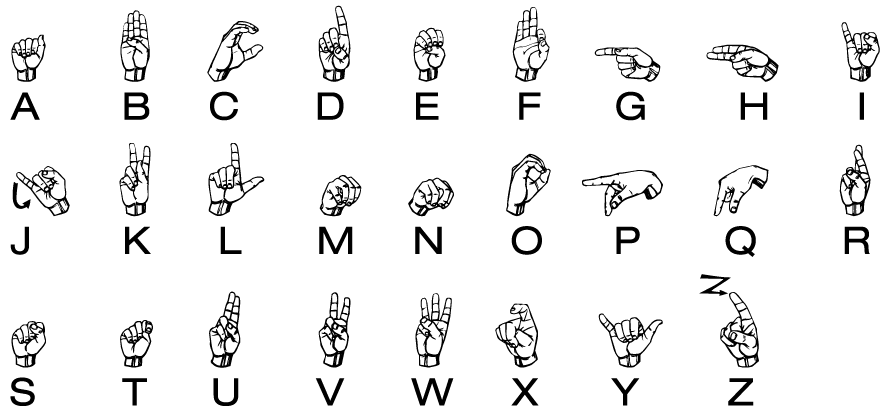

If either you or someone you love hails from Philadelphia, you know about the regional accent. It’s an intonation that turns “water” into “wooder” and “eagles” into “iggles.” Love it or hate it, the Philadelphia accent is a hallmark of living in the City of Brotherly Love. So pervasive is this accent, in fact, that even deaf people using American Sign Language have their own version of it.

American Sign Language looks different when it is spoken by someone from Philadelphia.

People who speak ASL are known for having their own dialects or “accents,” which have to do with the way that they sign words. Areas all around the United States have their own regional ASL dialects, but Philadelphia is known for having one of the (if not the absolute) strongest. Now, two researchers based out of the University of Pennsylvania are studying the Philly ASL “accent” for the first time and trying to figure out why it exists.

Meredith Tamminga and Jami Fisher are the professors conducting the research. They say that regional differences in American Sign Language are similar to how some Americans say “pop” and others say “soda” to mean the same thing. Fisher adds that many words in Philadelphian sign language are completely different from their standard analogues. The word for “hospital,” for example, is completely different in Philadelphian ASL, and the difference can be confusing to speakers from other areas.

One observation made by Tamminga and Fisher is that Philadelphia’s sign language is closer in many ways to French sign language than ASL. The first sign language teacher in America, Laurent Clerc, was a Frenchman. While ASL has moved on to have its own nuances and lexical variations, Philadelphian sign language has stayed more French.

Fisher and Tamminga will interview 12 Philadelphian sign language speakers from different generations and make painstaking analysis of the hand movements that make up their signs, a process that can take two hours for every minute of sign language recorded.